Is TEAM-CBT suitable for children and teens?

Although the basic framework of TEAM-CBT applies, significant modifications do need to be made to the approach for it to be useful with this population. There are special challenges and rewards when you work with children and teens because of their developmental stages. It is not helpful to treat them as mini-adults and simply use the techniques designed for adults.

I was thrilled to have the opportunity to explore this question in a specialised training group over two days with nine psychologists at Good Start Psychology. Their questions made it a thought-provoking, and enjoyable training session which left me feeling very positive about the future of psychology. The critical analysis, creativity and enthusiasm of these early-career psychologists was inspiring.

The most important consideration is to involve the parents or carers in the therapeutic process. The child is unlikely to seek therapy, instead, they will probably be brought to see a professional to fix a problem which has been identified as undesirable by the family or the school.

This makes the work more complex and much of it could involve parent training on behaviour management, routines, and communication skills.

It is essential to remember that you have more than just the child in this program. It will work so much better if you can enlist the support of caregivers to assist with homework tasks or review the strategies you are working on with the child.

What stays the same in working with children or teens?

It is beneficial to use the TEAM framework with this population but modifications in your language and materials will need to be made at every step.

Let’s look more closely at the changes needed to enhance the materials developed by David Burns and the Feeling Good Institute.

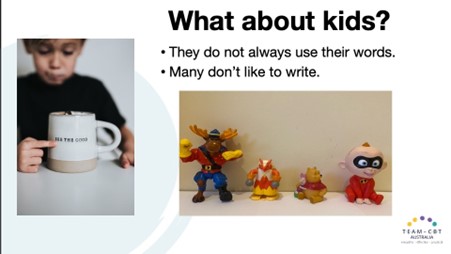

Testing: there are some child-friendly versions of testing materials available in the standard toolkit which can be purchased from the David Burns website. However, they still require a level of literacy which could be challenging to some children especially those with learning disabilities because it feels like schoolwork.

Instead, children can be actively involved in choosing a character with a clear emotion to represent how much they liked the session or how much they learnt. The line-up of figurines at the top of this blog is one such scale. Also, “Kimochi “ toys, shown above, help children to readily express and identify emotions.

If you have a wriggly 5-year-old with ADHD, another option is to have 3 hoops on the floor with the grumpy, ok or happy faces. The child can be instructed to run and jump into the hoop which shows how they felt about the session, how well the therapist listened, or how much they want to try out the new tricks they have learnt.

In this way, you get the feedback and the child stays engaged.

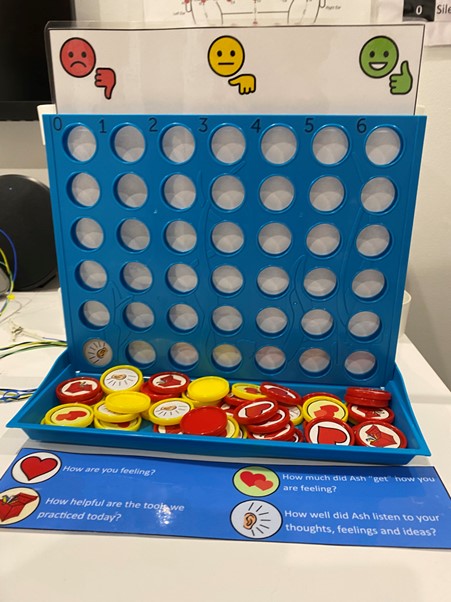

One of my favourite adaptations was developed by Ashlee Breen-Ellis. She turned a Connect 4 game into a feedback machine. It was a simple 3-point scale of Thumbs Up, Thumbs Down, or So-so (middling). Her clients were encouraged to use this at the end of the session. One young man got up, went to the device, and said “You are not listening!” Then he posted the appropriate token in the red column. Testing in that way provides us with immediate information and feedback so we can adjust the course and improve the session.

Empathy: These skills are universal across age groups. It helps to keep up to date with the latest music, shows or fads so your teenage clients don’t need to explain their world to you.

Agenda Setting or assessment of resistance: These techniques are the standard TEAM-CBT approach with adults but are even more important to avoid power struggles with the teenagers because most of these clients are not attending voluntarily. You need to find out what they are willing to work on.

Methods: You can use the standard resources and techniques when you are working with the parents.

One powerful technique to use with parents who may have unrealistic expectations for their children but really want to improve the relationship is to do Forced Empathy. That involves the parent pretending to be the child and speaking honestly about his/her feelings about the parent to the therapist who plays a supportive stranger they have met on the bus. The proviso is that the parent needs to have taken a whole vial of truth serum before answering any questions.

Usually, this results in the parent developing more understanding of the child and having much more compassion towards their difficulties.

Most standard methods can work with older teens but need to be both simplified and jazzed up for the younger ones.

The “Toolkit” provides a simpler version of the thought record or the Daily Mood Log with helpful instructions for parents. In my experience, you will need to spend time simplifying the concepts still further. Stories can be used to teach cognitive distortions or stinking thinking. These ideas will need to be repeated many times with different scenarios.

The challenge is to keep the methods playful and engaging. I was impressed by another Good Start psychologist saying that they could have the distorted thoughts written on paper and then use baking soda to demonstrate the fizzing up of that unhelpful idea!

Incorporating concepts into games and making social skill stories in Snakes and ladders format is also helpful. It is also possible to develop a cartoon avatar of the client for comic strip stories of challenging situations and choices they could make.

The only limit is creativity and ethical guidelines.

If any of these ideas appeal to you and you would like to learn more, please contact me to organise further training in this specialised area.